Finding the Right Supply Chain for your Product!

This again is an old classic in supply chain risk literature. In 1997 Marshall L. Fisher published this article in the Harvard Business Review targeting a simple question: “What is the Right Supply Chain for Your Product?”

It is noteworthy that this appears to be one of the most often cited papers in supply chain management. So I overlook the fact that it is quite weak on the methodological foundations.

The full text of this paper can be found here.

Product types

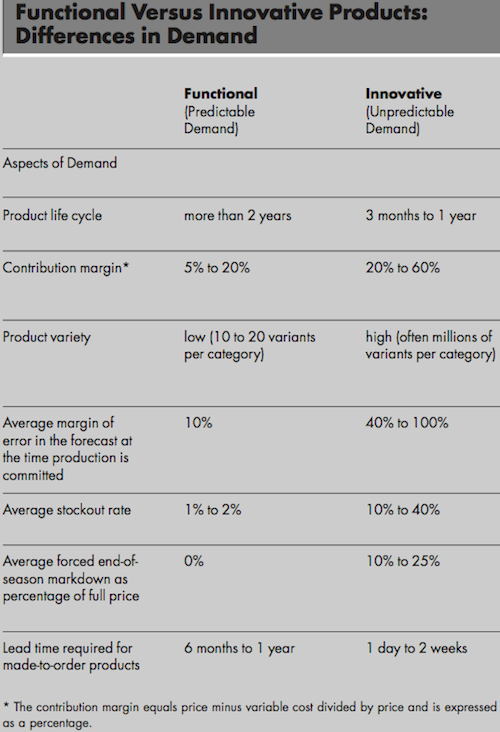

One of the major highlights of Fisher’s work is its simplicity. The author defines two basic products: functional and innovative products (figure 1). The major differentiating factor is the uncertainty of demand: Functional products (e.g. a classic Coke) show a rather predictable demand pattern and have long product cycles. Innovative products on the other hand show an unpredictable demand, and the life cycle can be as short as a few month.

Supply chain types

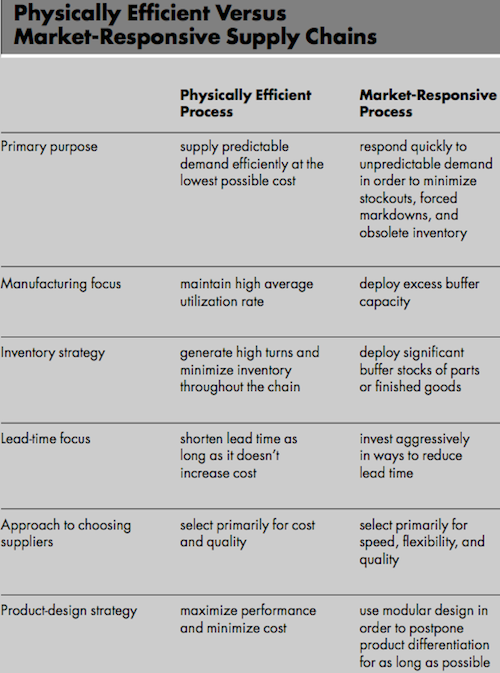

Staying in the realm of simplicity Fisher also sees two basic types of supply chains or supply chain strategies a company can select (figure 2).

First there is the Physically Efficient Process, which can supply a specified amount of products at the lowest cost possible.

Second there is the Market-Responsive Process, which focusses on quick adaptability towards changing market needs.

Strategic Implications

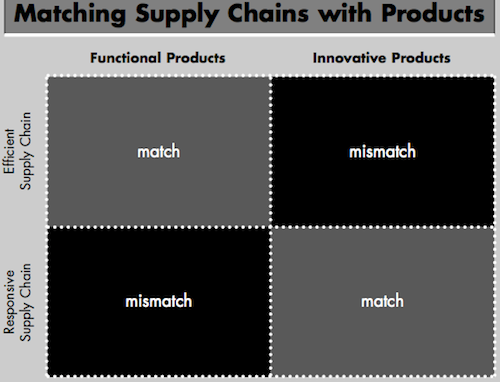

The strategic implications become obvious quite quickly. One does not want to match a efficient supply chain with a fast changing market, since this would probably leave the company either with a huge excess inventory or, if too little is produced, with many unsatisfied customers.

On the opposite side one should not match a responsive supply chain with a steady market demand. Cost for maintaining this flexibility are potentially to high to maintain a positive product margin.

Figure 3 shows the matches in a matrix.

Conclusion

The implications of this concept are intriguing, just define the type of your products and adapt the supply chain accordingly. Fisher validates his points by describing two case studies (Campbell Soups and Sport Obermeyer) where his concept was successfully employed.

On the other hand, the concept is really simplistic. There are overlaps in the defining factors of the process and product categories making them harder to separate than it seems: What really is a predictive demand and when is it unpredictable?

And the critique continues. In 2011 Perez-Franco, Singh and Sheffi documented some of it in their article (which I reviewed here), which indicates that the concept is not viable in reality.

Of course this does not mean that I underrate Fisher’s contributions: with this article he still contributed to the discussion of supply chain strategy and its influencing factors and it serves as a basis for many more works, as I mentioned above.

The conclusion I draw:

- Consistency: Of course there should be a connection between the product of a company and it’s supply chain strategy. But there are many other factors which have to influence an effective and efficient supply chain design as well.

- Methodological: Never rely solely on a handful of sample case studies as the foundation of a concept. Sometimes you will be right, but very often you will be wrong.

You can continue reading on Discovering the Right Planning Approach for your Supply Chain.

Fisher, M.L. (1997). What is the Right Supply Chain for Your Product? Harvard Business Review, March-April, 105-116

Add new comment